Projected Decline in Drug Overdose Deaths: 5 Questions with Stephen Patrick, MD

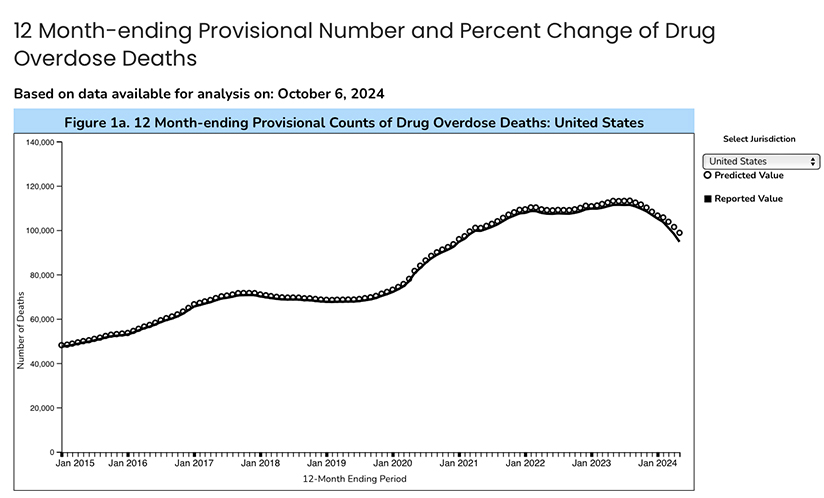

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released preliminary data last week predicting the number of drug overdose deaths nationally fell by a record amount (12.7%) from May 2023 to May 2024.

While this steep reversal in trajectory is indeed a cause for optimism, Stephen Patrick, MD, chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management, explains why it is critical to be cautious when interpreting this data.

Why is this reported drop in overdose deaths significant?

We saw a record rise in drug overdose deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, with deaths exceeding 100,000 per year. Within the last few years there were subtle decreases reported, but they didn’t look like this. What is stunning about these new data, is how substantial of a decrease this is, and that it is really the first major decrease we’ve seen since we began tracking drug overdose deaths during the opioid crisis.

What may have contributed to such steep decline?

It's important to note that we don't know the exact reason for the decrease in overdose deaths. There has been a real shift in the way we approach the overdose crisis. For example, there has been more focus on providing treatment with medications for opioid use disorder, which we know reduce the risk of death by as much as 50%. We’ve also had increased attention on distributing naloxone, which can quickly reverse an overdose, and on things like putting out fentanyl test strips to the public. So, there’s been this intentional focus that shifted toward including more of a harm reduction approach instead of primarily focusing on prevention alone.

What does this data not tell us about the decline in drug overdose deaths?

This is why we need to be cautious about how we interpret the data. Our harm-reduction approaches are working, but this significant drop might also be due to other factors. For example, I am worried there was such a rapid rise in deaths, and things remained so severe for so long, that there are now just fewer high-risk individuals around to have an overdose death. We didn’t save them while they could be saved, so now there are fewer people to be counted. These data also do not reflect important factors such as the number of non-fatal overdoses, or the number of people who entered treatment for substance use disorder. They also don't tell us about the downstream effects like foster care placements or people with long-term unemployment because they have substance use disorder and can't get into treatment. There are so many consequences of the opioid crisis that this data does not tell.

How does the number of drug overdose deaths now compare to other U.S. public health crises?

This is another reason why we should be cautious in how we interpret these data; we still have extremely high levels of overdose deaths even by any modern standards. I worry about taking our eye off the ball, because we still have a lot of work to do. There are still 95,000 people a year dying from drug overdoses. That is about twice as many as those who die in motor vehicle accidents about the same number as diabetes-related deaths in a given year. That is a powerful comparison because when we talk about access to insulin for diabetes, we don’t even bat an eye. But when we talk about access to lifesaving medications for substance use disorder, we make it very hard. We've seen policies change where we put caps in place for how much people pay for insulin. We haven't had the same drive when it comes to opioid use disorder.

How does the general public benefit by the rate of drug overdose deaths dropping?

This crisis has lasted for so long now that almost everybody knows someone who suffers a substance use disorder or has died from an overdose death. It affects all communities, it affects our neighbors, it affects our family members. The ripple effects of the opioid crisis are profound. It starts with deaths, and it extends to multiple spillover effects for such a broad spectrum of our country. For example, we see the opioid crisis leading to rises in children placed in foster care. We need to care about this crisis as a public health imperative, because it is not only killing people, but it is also affecting the very fabric of our families and our communities.