Study Finds Residents of Georgia County Have Elevated Toxic Chemical Exposure

A newly published study led by researchers at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health found that residents of a coastal Georgia county—home to nearly two dozen Superfund sites—have elevated levels of industrial chemicals in their bodies.

The study, which was published Friday in Environmental Pollution, offers a rare look into community-level human exposure to banned toxicants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and pesticides like toxaphene. It found that nearly 40% of the study participants had levels of a highly chlorinated PCB in their blood that were above the estimated national 95th percentile of the US population, with some individuals having exposure many times greater than this percentile. More than 20% percent of the participants also had toxaphene levels above the 95th percentile values.

“These chemicals have been in the environment in this area for a long time, but to our knowledge this is the first study to show that they have entered peoples’ bodies, and persist at levels substantially higher than what we would expect in the general population,” says Noah Scovronick, PhD, the study’s co-lead author and associate professor of environmental health at Rollins.

A Community Burdened

Situated on Georgia’s southeastern coast—between Savannah and Jacksonville, Florida— Glynn County has a long history of industrial pollution. Its county seat, Brunswick, is home to 23 Superfund sites, including four that are on or proposed for the EPA’s National Priorities List.

These sites are contaminated with toxic substances like PCBs, toxaphene, and mercury. Pollution from these sites has in some cases spread to local soil, water, and seafood. PCBs are a group of chemicals strongly linked to cancer and can also harm the immune, reproductive, and nervous systems. Toxaphene is a probable human carcinogen.

Despite the area’s history of environmental contamination, the Emory-led study is believed to be the first human biomonitoring study to assess the community’s level of exposure to these toxicants. The research found that exposure levels to several PCBs were significantly higher in older participants, Black participants, participants who reported fishing, and possibly in people who worked at the LCP Chemicals Superfund Siteand/or lived with someone who worked there.

“This pilot exposure assessment is a critical first step in evaluating potential health risks related to these exposures. By documenting the extent of chemical exposure, researchers can begin to explore how these elevated levels may be contributing to disease and other adverse health outcomes in the Brunswick community,” says Dana Barr, PhD, professor of environmental health at Rollins.

A Community Engaged

After representatives from the University of Georgia Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant alerted the Emory researchers that Glynn County residents were concerned about how their exposure to the chemicals could be affecting their health, the Emory team partnered with community organizations and local leaders to prioritize and respond to the community’s most pressing concerns.

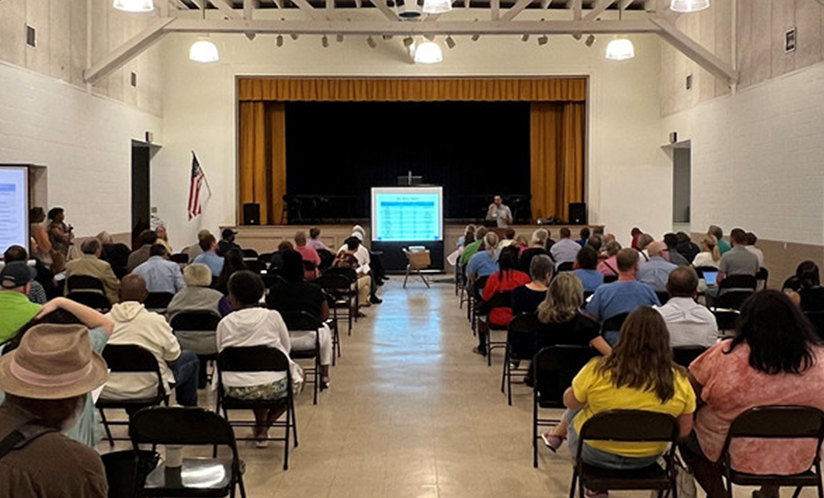

At a community fair in July 2022 hosted by this coalition – now called Healthy Coastal Neighborhoods—a clear majority (85%) of the residents indicated they were “highly” or “very highly” concerned about how contaminated sites were affecting their health. Many of those in attendance also said they preferred that research dollars be spent on testing the level of the chemicals in the bodies of residents, which informed the direction of the study.

For the community’s residents, the results represents both a confirmation of long-held concerns and motivation for the future.

Brunswick resident Anita Collins recalls the “beyond putrid” smell emanating from the nearby industrial plants during her childhood. She remembers breathing the air, drinking the water, playing in the dirt, and eating the local seafood.

“It was home. It's where I lived. … I did not know we were being harmed,” says Collins, adding she was “devastated” when she learned about the toxic exposure in her hometown. “I remain concerned about the harms we continue to inflict upon this planet. … What happened in Glynn County is not an isolated occurrence. We are human. We are still suffering. People should pay attention.”

Being able to provide the residents with the study results was also meaningful to the Emory team.

“For years, community members have been concerned about how industrial pollution may be affecting their health. Their voices shaped every step of this work and reminded us, as scientists, that behind every data point is a lived experience,” says Melanie Pearson, PhD, associate research professor at Rollins. “By returning the results, we’re not just sharing findings—we’re honoring a commitment. This partnership is built on trust, and together, we’re using science to lift up and address the concerns that matter most to this community.”