The State of Maternal Nutrition

The first 1,000 days of life—from the nine months of pregnancy through the first two years—is the most critical and vulnerable time where adequate nutrition for both mother and baby will have the greatest impact on short- and long-term health.

“We now have evidence that what happens during this period may have long-term consequences for the intellectual development of the child and the development of disease much later in life,” says Usha Ramakrishnan, professor and chair of the Hubert Department of Global Health. “If we don’t take care of women, we won’t have healthy child outcomes.”

Ramakrishnan, as well as several other faculty members at Rollins, have devoted their careers to researching and promoting maternal nutrition. The following highlights a few of their current and ongoing projects, advocacy efforts, and significant findings shaping public health policy and knowledge around food fortification, supplements, and optimal nutrition for women before, during, and after pregnancy.

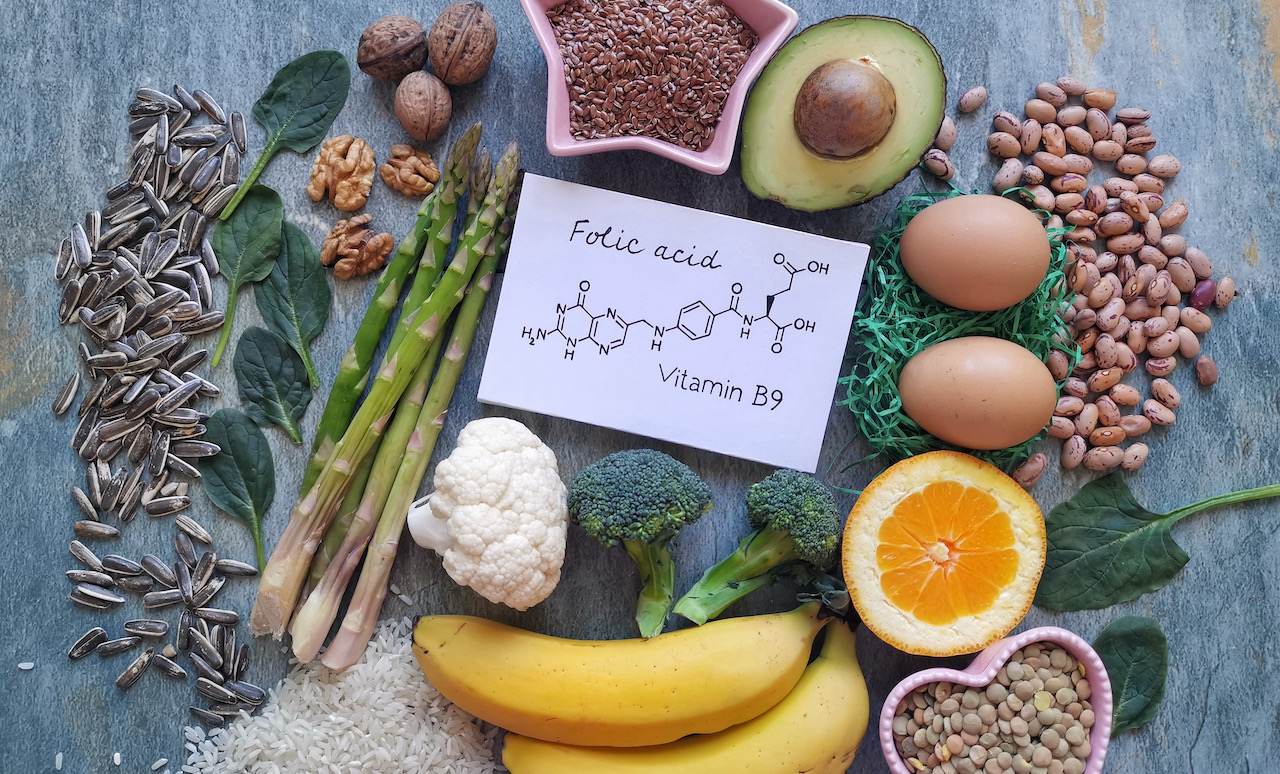

The Role of Folic Acid Fortification in Preventing Birth Defects

Godfrey Oakley, Jr., professor of epidemiology and director of the Center for Spina Bifida Prevention, is a worldwide expert on folic acid and how it can prevent neural tube defects. During his time as director of the Division of Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, he and his team were critical in persuading the Food and Drug Administration to mandate folic acid fortification of “enriched” grain products, such as bread, pasta, rice, and cereal, to prevent spina bifida, a disabling birth defect. Authorized in 1996 and implemented in 1998, the practice has now been adopted by many countries currently preventing about 60,000 affected pregnancies each year.

Despite this major improvement, many countries around the world have yet to follow suit, and Oakley’s message is stronger than ever. “There’s an enormous prevention opportunity that is being missed by more than 100 countries," says Oakley. "Every year, half a million kids around the world die or are paralyzed because their mothers live in a country where their government does not require mandatory folic acid fortification of a widely-eaten food. This is not a failure of any woman. This is a failure of their government. It’s public health malpractice.”

Birth defects occur so early—between 18 and 28 days after the sperm meets the egg—that starting folic acid supplements after a woman knows she’s pregnant is often too late. The CDC recommends that all women of reproductive age should have at least 400 micrograms of folic acid per day—the amount that is typically in a multivitamin.

Oakley and the Center for Spina Bifida Prevention have worked alongside the Food Fortification Initiative, which helps country leaders plan, implement, and monitor fortification programs, for more than 20 years to increase the number of countries which fortify foods with folic acid.

A recent win just occurred on July 1, 2023, when the Ethiopian government starting requiring wheat to be fortified. “You can easily tell if it’s working by measuring blood folate six weeks later. If it hasn’t gone up, then we know it’s not working. The resources to get things done in Ethiopia are meager. We need more big checks to deliver on this,” Oakley said of ongoing funding needs.

While major strides have been made in the U.S., Oakley noted that there are still opportunities to fill known gaps to prevent spina bifida. For instance, corn masa is not yet required to be fortified with folic acid. In 2016, a March of Dimes study convinced the FDA to allow the fortification of masa, yet many manufacturers haven’t done it. Therefore, Oakley said, women of child-bearing age whose diet is primarily corn masa flour-based foods may not be getting enough folic acid to prevent spina bifida, which is why research has shown that the blood levels of folic acid in the Hispanic population are lower and birth defects are higher.

In May 2023, the 76th World Health Assembly adopted a resolution calling for folic acid food fortification along with other micronutrients to combat preventable micronutrient disorders, such as spina bifida and neural tube defects, globally. Oakley and colleagues worked tirelessly behind the scenes to support and encourage a neurosurgeon advocacy team within the G4 Alliance. The Colombian Ministry of Health successfully sponsored, with 37 other member countries, the resolution that was adopted.

Oakley’s team at Rollins in partnership with Emory’s School of Nursing and community partners in Oregon, Ethiopia, and India, is also currently investigating how well adding folic acid to salt works to prevent birth defects. If folic acid fortification of salt is as effective as they hypothesize, folic acid fortification of salt will accelerate the global pace of preventing these disorders and may help many countries reach their 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

Studying the Impacts of Supplements in Pregnancy

In addition to folic acid, Ramakrishnan has been studying micronutrient supplements and omega-3 fatty acids to see if and how they play important roles during pregnancy. She is currently studying two long-term birth cohorts that are now in the follow-up phase: One looked at how taking multiple micronutrient supplements before pregnancy could affect birth outcomes for women in Vietnam. While the differences in birth outcomes were small, her team has found improvements in cognitive outcomes beginning at ages six or seven. The current work in the field continues to follow the children, who are now 11 years old, to look at school performance, body composition, and more.

The other study looked at how taking omega-3 fatty acids (400mg of preformed algal DHA) during pregnancy affected child growth and development. This 15-year study in Mexico found that the supplement is not a one-size-fits-all solution and birth outcomes largely depend on a woman’s predisposition. In the follow up, Ramakrishnan and her collaborators at the Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica assessed if the prenatal supplement affected children’s neurodevelopment at 5 years old, and found that there were significant variations, concluding that genetic makeup could be an important factor to consider for prenatal DHA supplements.

Ramakrishnan is currently very interested in women’s nutritional and health status at the time of conception, including the implications of having gestational diabetes, being overweight, or having a metabolic disorder. “They all influence how the pregnancy progresses and how it should be managed for optimizing outcomes,” she said. “This is something that’s being studied globally.”

Nutrition During Pregnancy and Postpartum

Amy Webb Girard, associate professor of global health, has spent the last 20 years working on programs and tools to improve dietary diversity and diet intakes among pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under 2 years of age. Her work in the design, monitoring, and evaluation phases of nutrition programs focuses on social and behavior change and strategies for creating enabling environments for women and young children to achieve optimal diets. Girard’s projects often are in collaboration with community-based organizations and NGOs that help shift societal norms for healthy foods, as well as agricultural organizations and traditional health organizations, such as CARE and Save the Children, which help with increasing the availability and affordability of healthy foods in food insecure areas.

“We have made good progress on child nutrition, but we are still not making progress in terms of women’s anemia, neonatal mortality, very young infant nutrition, low birth rate, and preterm delivery. The reason for that is we’re not moving the needle on maternal nutrition,” says Girard, who hypothesizes that is because women are often not prioritized for healthy foods in the mother-child dyad.

“Our work tries to develop tools and community-based strategies to put women at the center and to shift community norms so that women become prioritized for healthy foods,” she said.

In 2012, Girard and team developed a “Healthy Mother, Healthy Baby” first 1,000 days feeding toolkit with the support of a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant. The toolkit is essentially a very simple bowl that has markings to indicate how much extra food women should eat during pregnancy and breastfeeding and how much to feed babies from six months to 24 months of life. So far, it has mostly been used by organizations, such as UNICEF, for children and has received positive feedback from communities in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and India in terms of child diets, Girard reported.

This year, Girard received a grant from The Agency Fund to create a program to see how it impacts maternal nutrition. The randomized control trial will begin in January and continue for 20 months and includes Ramakrishnan and Melissa Young, assistant professor of global health, as co-investigators. It will enroll women in early pregnancy and follow them for nine months postpartum to measure weight gain in pregnancy, postpartum weight maintenance, dietary intakes, exclusive breastfeeding rates, how they transition the bowl to child feeding at six months, and child growth from birth to nine months.

“We had to really push [the donor] for women. Many organizations just want to focus on the child,” said Girard.

So how much should pregnant women eat? Girard said, in general, the recommendation is simple: one extra meal of quality foods, such as fruits, vegetables, eggs, nuts, and healthy sources of protein per day when you start to show or beginning in the second trimester.

But the hurdle is more than food insecurity and messaging telling mothers, “You need to do this.” In many cultures, it goes against societal norms for women to prioritize themselves over others. During the Mamanieva Project with World Vision in Sierra Leone, Girard worked with grandmothers, who were the real influencers of the community and had sway over the societal norms around maternal and child health. With these elder women in the community supporting pregnant women and new moms, they saw significant reductions in low birth weight and an improvement in women’s diets. Beyond this project, much of Girard’s formative research in communities helps to structure behavior change communication strategies that take a family-focused rather than mother-centered approach.

Despite much dedicated research and progress, a lot of work still needs to be done around maternal nutrition and factors that can affect it. “While nutrient interventions are critical, access to health care early on and prenatal care are also very important. Women should be counseled when they are planning to be pregnant. We need to have health systems where we reach women at the right times with the right information,” says Ramakrishnan.

Emory’s Nutrition and Health Sciences (NHS) PhD Program

Emory’s NHS program is a four-year doctoral program offered through Laney Graduate School that encompasses molecular/cellular and population/epidemiologic approaches. The goal of its curriculum is to provide students with the skills to investigate the relationship between nutrition and human health, with an emphasis on the prevention and control of nutritional problems and related diseases. As an interdepartmental program, NHS draws esteemed faculty from across Emory University, including Rollins, the School of Nursing, and School of Medicine. Learn More